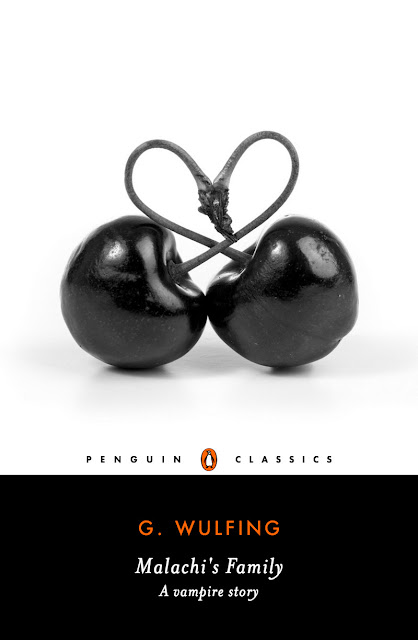

This is a fake book cover (made with the Penguin Classics Cover Generator) for my short story ‘Malachi’s Family’. The Penguin Classics Cover Generator is fun, and very easy to use.

You have reached the blog of G. Wulfing, author of kidult fantasy and other bits of magic. Visit my Smashwords page (linked below) to view my e-books, help yourself to the free ones, and subscribe to this blog or follow me on Tumblr for announcements of new ones.

Wednesday, 30 November 2022

Fake book cover for 'Malachi's Family'

Short story: Malachi's Family

One of them noticed a few children playing in a long-grassed field, on the other side of a bank that ran alongside the path. After a moment, he quietly pointed them out to the others, and the four men became stealthy as they approached the field, using the bank as cover.

There were three children, all blonde, and none looked over seven years old, dressed in simple tunics and trousers. There was a grove in the field, a short distance from the bank, and in the shade of the trees a man lay half-curled on his side, partially obscured by the stalky grass, apparently dozing or asleep; perhaps thirty or forty years old, tall and lean, with black hair and pale skin. He appeared unarmed, wearing trousers and a tunic in washed-out dark blue linen, with a black sash.

The four dirty men looked at each other, and with a few whispered words and some gestures, made their plan.

The children looked up as the men appeared swiftly at the top of the bank. They would have gazed in curiosity, but the men were already swooping upon them, booted feet crushing the long, half-dry grass, seizing the children around their waists, while a shaven-headed man, his curved sword drawn, ran straight for the dark-haired adult lying under the trees.

Terrified and bewildered, the children screamed. One of them shrieked, “Malachiii!”

The shaven-headed man was upon the dark-haired one in only a handful of strides, but suddenly his quarry had leapt to its feet and was standing upright, facing him, half a head taller than he, snarling and glowering straight into his eyes. A low, loud rumble or growl seemed to reverberate in the air: less a sound and more a vibration: an inhuman noise.

The dark-haired man’s clear grey eyes suddenly glowed red, and slim but very pointed fangs had appeared behind his bared upper lateral incisors.

No — not human at all. It was a vampire.

A moment later, the last corpse fell from the hands of the vampire, its neck having been emphatically broken. The vampire cast a look around himself, to ensure that all four of the twitching corpses around him were indeed corpses, their heartbeats gone. He rearranged his tongue in his mouth, feeling his fangs withdraw, tasting the slavers’ blood on his teeth. Then he looked for the children.

They were cowering among the trees. He could see their clothing protruding, and hear their frightened breathing. It seemed as though they hadn’t watched the end of the violence, which was good.

The vampire took a few steps toward them, sandals rustling the stalky grass.

“It’s over,” the vampire called calmly. “You’re safe now. They’re all gone.”

‘Gone’ was perhaps a euphemism — the broken, bloody bodies were certainly not gone — but the children would know what he meant. The slavers themselves, with their evil intent and greedy hearts, were gone.

The children hesitated. One of them peeked fearfully around the trunk of a tree. The vampire held out his hand.

Brown eyes wide and tearful, the child stared at him. “It’s fine,” the vampire said reassuringly, hand still extended. His voice was deep and modulated.

The child did not look reassured, edging back behind the trunk, her gaze flicking briefly down to the vampire’s chest. The vampire glanced down at himself and realised that he had blood spatters on his linen tunic, smears of blood on his hands, and probably more spatters on his face. This would not be helping to alleviate the children’s fear.

The vampire strode back to the bodies and picked up the nearest reasonably clean-looking garment: a red cloth cap. He wiped his mouth and lower face on it unsatisfactorily before dropping it. Realising that he would still have blood on his teeth, he snatched up a canteen from the belt of one of the dead slavers, unstoppered it and took a large mouthful, not caring what the fluid was. He swished the tepid water around his teeth and tongue, washing out his mouth, before spitting it out onto whatever grass or human body lay beneath him. He used more water to wash his face and hands. Then he stoppered the canteen, more to be tidy than for any other reason, and dropped it back beside its erstwhile owner’s body. He wiped water off his face with his hands, rather than using his blood-spattered sleeves. Then he approached the grove again.

“Children. You’re safe. It’s all over.”

He knelt in the grass, several paces from the trees, and waited.

“Malachi?” a small voice wavered timorously, after a moment.

“Yes?” the vampire responded calmly.

A different pair of brown eyes peeped at him.

Still Malachi waited. The sun and breeze began to dry the remaining moisture from his hands and face.

At last, the youngest of the children sprinted toward him, and even as Malachi opened his mouth to warn her that she might get blood on her if she touched him, her arms were wrapped tightly around his neck and she was half-sitting in his lap, snivelling her confusion and fright. The other two children followed immediately, clustering around him like chicks around their mother hen.

“M-M-Malachiii!”

“W-Why did they try to grab us?!”

“M-Malachi, I’m scared!”

He hushed them, soothed them, hugged and reassured. The older two glanced toward the bodies, found that their horror overcame their curiosity, and buried their faces in Malachi’s shoulders, blood spattered tunic forgotten or ignored.

The vampire would have let them inspect the bodies if they had so desired — he would have told them that this was what happened to bad people who tried to hurt the friends of vampires — but they clearly did not want to, and that simplified things.

“Shall we go home?” he asked, when the majority of the tears and panic seemed to be over.

The children nodded fervently, and Malachi shepherded them home. He would have walked in the rear as usual while the children skipped and scampered ahead or wandered alongside his long legs; except that this time they clung to him, gripping his fingers uncomfortably tight, casting nervous glances in all directions across the countryside. They no longer felt safe here, Malachi realised. Their wide playground of fields and hedges, in which the most dangerous thing that lurked was a poisonous toadstool or a stinging insect, was now a theatre of threat. The slavers had barely touched the children’s bodies, but they had done permanent harm to their minds.

Malachi wished he could have killed the slavers before they had ever set eyes on the children.

And while the children clung to Malachi as their ‘safe place’, even he was not truly safe to them now. He had killed in front of their eyes. The blood of humans was on his clothes. Their guardian was a killer, and though they held his hands, Malachi could see in the eyes of the older two children that they now feared him a little, too.

They would never be able to trust him quite the way they had before.

He hoped that the slavers would know no peace in the afterlife. People who robbed children of their peace of mind deserved to never feel peace again.

When the children’s home on the outskirts of the village came into view, the children let go of Malachi’s hands and sprinted for it as though they were being chased.

“Slavers?! Here?!”

The parents’ eyes were wide and their faces pale. They stood in the kitchen, the two older children clinging to their mother, while their father held and hugged the youngest, who was whimpering on his shoulder. Sawdust and wood-shavings dusted the man’s clothing: he had come straight from his workshop at the side of the house upon hearing his wife’s troubled summons.

“There were only four of them. Merely a roving band of villains. Opportunists. Not organised.”

“Did you — did you kill all of them?” the father asked.

The vampire frowned slightly and lifted his nose a little, his pride offended. “Of course. I said there were four of them, didn’t I? If there had been more, I would have killed more. There were four slavers, and now there are four corpses.”

“Thank you,” the mother said fervidly. “Thank you. Oh, Malachi … I can’t … oh, Malachi …” Her voice became choked, and she knelt and hugged the two elder children close.

The father’s eyes had filled with tears, and he clutched his youngest child tightly. He nodded his agreement with his wife. “Thank you,” he whispered, clearly unable to say more.

Malachi inclined his head in acceptance. He was glad of what he had done, and it had not been difficult; but he would always regret that it had been required.

He glanced again at the children, and again he execrated the slavers in his mind.

Then he turned to leave the family to their emotions for a while.

An hour later, the children’s father found Malachi in the small orchard at the back of the house, picking cherries and placing them into a basket on his arm. Malachi, now wearing a clean outfit, acknowledged him with a look, and the human man cleared his throat and spoke, a little huskily.

“We can’t thank you enough for saving our children, Malachi. We can never repay you for that.”

“You don’t have to. We have a pact, do we not?”

The father nodded.

“… We didn’t expect … I suppose we didn’t expect that you would have to kill to maintain it,” he said, after a brief pause.

“My part of the bargain is to protect your family, and that is what I did,” Malachi reasoned simply.

He added, “If I could have killed the slavers before they even touched the children, I would have done so.”

The carpenter nodded. There was a pause.

The vampire continued to select and pluck cherries.

The father was massaging the inside of his left elbow slightly. He took a deep breath and lifted his gaze to Malachi’s face. “This was a good bargain.

“I know there are some who think it strange that we associate with you, but if all it takes to keep my family safe is a few mouthfuls of blood, I would give it a hundred times over. I would give all of it to secure for them a guardian like you.” He held the vampire’s gaze. “They may have nightmares for weeks; they may never feel completely safe ever again; but because of you, my wife and I will be there to comfort them. If it weren’t for you, Malachi — If it weren’t for you —” the man’s voice cracked — “we wouldn’t have them at all. And I would never sleep again.”

The vampire gave a slow, gracious nod of acknowledgement.

There was another, longer, pause, during which Malachi resumed his picking.

Then the human man fidgeted slightly. “What — What shall we — Do you … Erm, have you any need for the bodies?”

The vampire looked at the carpenter, a little superciliously. “Do I want their blood, do you mean?” The human nodded, and the vampire made a noise of scorn. “Tchah. As if I would drink from scum like that.

“Besides, I already have everything I need.”

As he reached upwards for the next cluster of cherries, he looked over his shoulder at the human man, and though his lips were not exactly smiling, his clear grey eyes were shining.

End.

Thursday, 11 August 2022

Poem: To Luna

To Luna

24 March, 2008.

Sunday, 31 July 2022

G. Wulfing’s favourite writing tools

Writers, nowadays, have a host of resources and tools at our disposal. I admire the authors of the past who had nothing but pen and paper, or stylus and clay, and I firmly believe that masterpieces can be created in spite of practical limitations; however, in the age of endless distractions, anything that makes concentrating and organising one's thoughts easier is welcome. Below are brief descriptions of my favourite tools.

Scrivener.

I love this software. It’s designed by writers, for writers, and it has everything I could desire in a piece of fiction-writing software. I bought a Mac-compatible version for about fifty New Zealand dollars. I don’t use all the features (incidentally, I’m told that some writers use even fewer of Scrivener’s features than I do), but that’s not the point: what I do use is fantastic. It makes writing faster, easier, and more efficient than using multiple Word documents for each story, which was my previous technique. A bonus: it’s pleasant to use and actually makes me feel more professional and in control. According to the website, it’s great for non-fiction writers too.

Candles and rain sounds or other ambient noise.

For reasons explained here. The short version is that the rain soundtrack, or similar ambient noise, keeps my brain distracted enough from the silence that it can focus, but not so distracted that it abandons writing altogether. There are many websites that supply beautiful, atmospheric ambient noise, often with customisable settings.

Masala chai lattes; hot chocolate; hot chocolate with coffee.

In descending order of healthiness, those are my three favourite beverages to drink whilst writing. I’m not sure that my progress would be what it is if not for those three. I like most types of tea, but they just don’t have the fullness and body that I seem to require from a drink when working. I started making and drinking masala chai lattes with raw honey in an effort to break my beloved but too-sugary habit of two cups of hot chocolate — with or without added coffee — per day, and it worked. I have now replaced the sugary hot chocolate with a sugar-free chocolate mix, with coffee and full-fat milk, but I still keep my first love in reserve for when I need something extra hefty to get me through a painful edit or an all-nighter.

Smashwords.

Best. Publishing. Platform. Ever.

In all fairness, I’ve never tried any other. But I see no need to. In order to publish a book, I upload an appropriately-formatted Word document to Smashwords, plus a cover image, and thereafter Smashwords does all the work for me. My single document is transformed into multiple formats that work on a host of different e-reading devices, and are distributed to assorted online booksellers without any further effort on my part. A couple of days or weeks later, I can search the Internet for my newly-published book and see it sitting on virtual shelves.

My soulmate’s intellect.

My soulmate is the only person I allow to see my work before it is published. He was a published author many years before I was, and he is, to date, the only person I trust to give me feedback. I don’t run every story past him, but the vast majority of them are read by him before being published. I can ask him difficult questions and he will give me considered, respectful responses that make his point without offending my delicate, drama-queen ego too much. If everyone had a friend like him, the world would be a better place and we would all be better people.

Wednesday, 27 April 2022

A few more of my pet peeves in fiction

Last year I wrote in this post about some of my pet peeves in fiction, and I wanted to make this post a counterpart and discuss some of my favourite things in fiction ... but all I could think of were more pet peeves. So here is a second round of annoyances, and perhaps one day I will be able to think of some more positive things.

Prophecy. The Chosen One is prophesied to do something or other, and often the exact nature of the prophecy barely matters: the point is that someone is Chosen by something — probably destiny, which I ranted about in the previous post of this nature. But who makes these prophecies? Where do the prophecies come from? How are they communicated? Does someone write them down in Ye Massive Notebooke Of Prophecies That We Fulley Expecte To Come Trewe? Why do people believe them? How many are there? What happens if prophecies clash, or seem mutually exclusive? What happens if a prophecy is proven wrong? Who determines whether a prophecy has been proven wrong or if it simply hasn't come true yet or if it was misinterpreted in the first place, and how? Prophecy as a trope typically seems to be used merely to spackle over holes in plots and premises, but if I think about it for five seconds it invariably raises more questions than it answers.

Vows broken for shock value or comedy. You've heard of Chekhov’s Gun; I now present to you:

- Chekhov's Virgin (this character will not be by the end of the story)

- Chekhov's Vegetarian/Vegan (this character will break from their diet by the end of the story)

- Chekhov's Vows Of Celibacy (said vows will be broken by the end of the story) (Actually, this could simply be called "Chekhov's Vow": any vow made or mentioned within the story is at high risk of being broken)

- Chekhov's "I Don’t Like Children" (the character who says this will be forced to interact positively with children by the end of the story)

- Chekhov's "I Will Never In A Million Years Do That" (the character who says this will, by the end of the story, absolutely have "done that")

I dislike this trend, for several reasons. It cheapens the vows, particularly when they are broken easily and without consequence. It feels like denying characters agency: the character states that they do not want to do a thing, so the author snickers and deliberately makes them do the thing. I am aware that fictional characters are fictional and therefore cannot be bullied, but for readers who have been bullied or teased for being or saying any of the abovementioned things, it is upsetting to see narratives inflicting on fictional people what real people have inflicted on them, the readers, in real life. It often seems like the author is deliberately inviting the reader to laugh at the character for having the audacity to make vows, or state firm preferences; as though we, the readers, are being expected to join in the mockery. Moreover, it is, of course, transparent and predictable: the moment a character declares that they don't care for children, I brace myself for the arrival of their interactions with children.

The Girl™. "Here is our cast of main characters! They all have personalities! We have an aloof, serious one, a sensitive, hotheaded one, a charming, roguish one, and a girl. That's it: that's her personality: she is a girl. What does she do? What does she want? Well, she's a girl, so she falls in love with one of the main characters, because that's what girls are for. Her motivation in the story is that she has a crush on one of the male characters, because girls never want anything besides romance. She doesn't need to participate in the plot or have any character development: she's a girl."

"They'll be okay. They're a fighter." This is invariably spoken, with intent to reassure, when the protagonist, or a supporting character, is ill, injured, or unconscious. It bothers me for multiple reasons. Firstly, we are all fighters. Everyone who has survived their life up to this point is a fighter. "He's a fighter" — and you're not? I'm not? His great-great-great-great-grandmother was not? Secondly, being a fighter or being tenacious is no guarantee that anyone will be okay. There are plenty of people who fight for their lives and lose. I have known people who seemed indestructible and endlessly vivacious, right up until they suddenly fell ill and died within a week. They fought to live, and fighting did not save them. Everyone is a fighter in some way, and being a fighter will not make you okay.

Unconvincing or unnecessary romance. I could write an entire thesis on why most romantic subplots in fiction are ghastly, but it would just be infuriating. Romantic love saves the day/world! (Despite the fact that, in context, it should not be able to!) This character is incomplete without romantic love! This character who met their love interest two days ago is now ready to marry them and will be miserable forever without this person they met two days ago! Romantic love is not magic; it is not the be-all and end-all of everything; people — real or fictional — who are without it and/or are not interested in it are not incomplete or lacking in any way; and it is not the same as attraction.

Unrealistic injuries. I once read a conventionally published fiction book in which a horse took three arrows to the belly. The horse not only survived but required zero medical attention and the arrow wounds were never mentioned again. The narrative gave them all the consideration of mosquito bites. In reality, a single arrow embedding itself in the belly of a horse could be fatal and would require immediate expert medical attention and probably surgery. Even a grazing wound or a nick should have been inspected and treated. If your character gets shot or stabbed or even badly bruised, there should be consequences. Any kind of breakage or sprain could require months of treatment and rehabilitation, and the body part may never be the same again; moreover, other parts of the body often suffer under the strain of compensating for, and preserving, the injured part: for example, if the left ankle is injured, the right knee and hip joints may be strained or even damaged from having to take the full weight of the body, and the spine — including the neck — may become misaligned due to the stress of limping. If you're going to injure your characters, either treat the injuries realistically or explain how they were magically healed two days later.

Super-rapid skill gain. It takes years to become good at longbow archery. It takes years to become good at weaving, swordfighting, herbal medicine, piloting, horseriding, speaking a language, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera; and even after a certain level of skill has been reached, mistakes will still occur. People who have been studying Spanish for three years will still have misunderstandings, forget words, and make grammatical slips. Natural talent is helpful, but it is not a substitute for practice, tutoring, or experience. If a character suddenly becomes a skilled archer, surgeon, or mathematician in the span of three days, I want a very convincing explanation as to how.

Wednesday, 23 March 2022

Poem : Human Loves Me

Human Loves Me

September 2020 to 29 April, 2021.

Monday, 28 February 2022

On the opening lines of stories

Here are my opinions, as a reader, on opening sentences and first paragraphs in fiction.

Starting in medias res is not necessarily a bad thing, but generally I like to be eased into the story. Dropping me into the middle of a scene I'm supposed to care about and assuming that I will start to care within 0.3 seconds is ... well, sometimes it requires more emotional energy than I have spare.

The dragon gave a roar, and blasted Bob with its fiery breath. In the next moment, it smashed the house with its tail. The shockwave blew Bib and Beb backwards —

Oof. I'm exhausted already. Should I care about Bob? I don't know. How big is the dragon, exactly? I can't picture it because I have no description of it. Likewise, what house is being smashed? Is it Bob's house? Who or what are Bib and Beb? I am potentially interested in dragons blasting and smashing, but you have given me no time to understand what is really happening or why. Is the dragon justified in blasting and smashing, or is the dragon the villain? I don't know how to feel about this. You have given me no time to become engaged.

The phrase "Once upon a time" is actually brilliant: it's a cliché, yes, but — like many clichés — it works. It gives me a moment to get settled in. It invites me to take a breath and focus on what I'm about to be told, and it has a reassuring humility to it.

"Once there were four children whose names

were Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy." Great: a simple sentence

that tells me the names of our four main characters and that they are

children. (The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe, by C. S. Lewis.)

"In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit." Also great.

Setting and character, both introduced in a very straightforward, unthreatening

way. Tolkien, bless him, then immediately describes the hole, and the hobbit, rather

than leaving me in frustrating suspense over what the setting is like and what on

earth a hobbit is. (The Hobbit, by J. R. R. Tolkien.)

"Call me Ishmael." Righto, will do. (Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville.)

"I am an invisible man." Marvellous. Do go on. (The Invisible Man, by H. G. Wells.)

"Marley was dead, to begin with." Spiffing! Who's Marley? (A Christmas Carol, by Charles Dickens.)

I

am generally in favour of keeping the first sentence simple and decisive. If I am reading a

story for the first time, I have never met it before; it would be nice

if it said hello and introduced itself clearly in nice plain language

before it starts expecting me to keep up with its antics of plot

and suspense. I would like to be spoken to politely before I am asked to

care and attend.

"It is a truth universally acknowledged,

that a single man in possession of a great fortune, must be in want of a

wife." This is a more complex sentence, but the ideas in it remain simple, and its tongue-in-cheek humour introduces Jane Austen's style and tone so

perfectly that it is the ideal advertisement for the rest of the book. (Pride And Prejudice, by Jane Austen.)

There are some brilliant, complex opening sentences. I am not complaining about long or complex or wittily wordy opening sentences. But I very much prefer it when even a loquacious opening illuminates the setting or introduces a character, rather than simply dumping me into the action.

It was five o'clock in the afternoon when the earthquake hit.

This has a similar feel to "Marley was dead, to begin with". It is a strong, simple opening statement about an event that, it is implied, is important to the rest of the story. However, what follows it is important: you better be about to give me every detail

about this earthquake, because if you introduce something as intense as

an earthquake and then leave me in suspense about it I am going to be cross.

It was five o'clock in the afternoon when the earthquake hit.

... But the earthquake is not what this book is about.

THEN WHY DID YOU WASTE MY TIME BY MENTIONING IT. Two sentences in and I'm already annoyed by your story.

It was five o'clock in the afternoon when the earthquake hit.

But the earthquake wasn't that big a deal, as it only rattled the teacups in the china cabinet, which caused Mother to remark that we never used those teacups anyway and that she wasn't sure why we still kept them, as they were an old anniversary gift from Aunt Mabel, who always did have the most terrible taste.

Hmm. I might be interested in the teacups and Aunt Mabel and Mother, but you baited me with the earthquake, so I am on the lookout for more shenanigans, and if you continue to use dramatic-sounding sentences to introduce mundane moments then you'd better do it masterfully so that it is a clever running joke — perhaps suddenly subverted at a critical moment for impact — rather than annoying.

It was five o'clock in the afternoon when the earthquake hit.

***

Six weeks earlier.

Caroline had spent the entire day on the telephone to various bosses and superiors, trying to sort out the mix-up with the Bradberg account, painfully aware that when she returned that evening to the apartment that she shared with her boyfriend she would no longer be able to hide the truth from him: she was having an affair with his mother and wanted him to leave. Sharon, Bobert's mother, was recently divorced, and almost old enough to be Caroline's mother, which made the whole situation even more sordid; but Caroline could not help herself: Sharon was magnetic, pulsating, vibrant, and enough of that magnetism and vibrancy had been passed on to Bobert that Caroline had been attracted to him immediately. It was only after dating him for eight months that she realised that she was enjoying the occasional coffee dates with his mother more than she was enjoying her relationship with Bobert. He was endearing, sweet, and Caroline felt bad about breaking his heart, especially after he had paid for the apartment out of his life savings, but ... well. The heart wants what it wants, as one of those poems she had been compelled to learn in the fourth grade had said. Miss Collins had looked vaguely sad as she read that poem aloud, and Caroline had never understood why; eventually she had chalked it up to that ennui that so many fourth-grade English teachers possessed. After all, something must make them sufficiently weary of life that they decided to teach fourth-graders.

On hold, Caroline fiddled with a pen on her desk. It was inkless, barren, one of the ones she kept intending to throw out and never did, instead leaving them crammed alongside all the functional pens into a novelty Snoopy mug on her desk, given to her by her best friend Brenda as a cheap souvenir from Australia. Somehow, it felt easier to throw out a boyfriend who bought her an apartment than it did to throw out a dry ballpoint, or even a tacky souvenir mug. She wondered what was wrong with her. Was this the midlife crisis that people kept talking about? She was only twenty-seven, she shouldn't be having a midlife crisis yet, surely. Maybe she was deficient in something — magnesium, or vitamin K; maybe she was bored with her life and needed a change; but dumping Bobert was —

Oh, my gosh, go back to the earthquake and kill Caroline with it.

The bafflemakers had run dry, again. Gilly and the other Bogbrains cowered in the stormruns until the groatwalkers had shambled on their way, then slinbl'd their gel-powered spacebikes across the waffled blinkroad, quick and quiet as spelunking Pumerian salmoncats. It was too early for the Dome to be illuminated, so they utilised their glowlamps to pass as chillsprinters, and blapped the glumonkeys chipplingly.

I don't know what any of this means. I can't care about it if I don't know what it means. And the writer is making a large gamble about how long I am willing to wait before they explain what all these things are. You don't need to keep me in suspense about what a blinkroad is; I am already in suspense over what bafflemakers are, and why they have run dry, and whether this is a problem, and, if so, for whom. You have already given me several burning questions in your six-word opening sentence: adding more mysteries just overwhelms my desire to know any of the answers. By the time I have figured out what a bafflemaker is, I will have forgotten about everything else that was mentioned, rendering this entire paragraph little better than white noise.

"The bafflemakers had run dry, again" is perfectly serviceable by itself, just like "In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit." The difference is that Tolkien promptly explains to us what the hole is like and what a hobbit is, rather than piling on another sixteen unknown words before he explains the first one.

I think one of the key differences in whether I find an opening line annoying or intriguing is whether it shows some humility and courtesy. Is the author showing off how many words they can invent, without regard for how confusing and unhelpful that may be for the reader? Is the author expecting me to care without first giving me any reason to do so? Is the author making me wade through five paragraphs, or even five sentences, without explaining anything about what is going on?

I am firmly of the belief that art, including writing, is for the artist, not the audience. However, if the artist wants the audience to enjoy the art, the artist needs to give the audience some consideration, and I would posit that such consideration is especially crucial at the beginning, for if the beginning is off-putting, the story will probably be abandoned, no matter how good the following pages are.

Saturday, 8 January 2022

How to recover from a Winter; or, How to resume writing after writer's block and burnout

For five years, from 2016 to

2020, I experienced what I call a "Winter": a period of

sustained writer's block, topped off, in 2020, by emotional burnout, as so

many people on this planet have been experiencing. In 2021, at last, I managed to slither out of the dank, miserable hole of

I-Can't-Write. Recovery is slow, and ongoing, but it is happening, and I am delighted.

I

had drafted a lengthy blog post offering some advice on how to recover

from a block/burnout, and what that process is like; and then my

computer crashed, and I lost the whole thing. (Incidentally, have you

backed up your writing today? If you haven't, do it now. If you have, do it again.)

So I shall write it again, because I feel that many of my fellow writers could benefit from such a blog post, if only for future reference.

And I have a nasty little suspicion that I may need it again myself, someday.

Step 1: Stop panicking, and stop trying.

Creativity comes in surges and seasons; this is a well-known fact among people who have been engaged in creative practices, such as writing, for a long time. It would be wonderful to be always aflame with creativity, always inspired, churning out work as fast as we can ... but that is not how the world works. Spring does not last all year, and your psyche cannot work at peak productivity all the time.

If you are grieving, stressed, processing some trauma or other, dealing with any mental illness or disability, or just coping with some significant change in your life, that will be hogging your mind's energy, and perhaps burning all your soul's reserves. It is normal.

So stop trying to write. Your brain is telling you that it cannot. You want to write, don't you? If you could, you would; the fact that you aren't means you can't.

You will write again. It's okay. It is likely that the more you panic, the longer it will take you to be able to write again. You are still a writer; a cup is still a cup whether it be empty or full, and a pen is still a pen when it has run out of ink. Plenty of writers throughout history have stopped writing for years, or even a decade or two, before resuming.

Step 2: Rest.

Your soul lives in your body, and what happens to your body affects your soul. You need a rest, both physically and mentally. It is time for some serious self care, my friend.

How's that sleep schedule? When did you last lie on the couch and do nothing? Do you need a nap? Sleep is one of the most powerful, most underrated, most ignored needs of the body and soul. There is plenty of research to support this.

Have you been eating a lot of junk food recently? How much water are you drinking? Your brain is an organ just like your gut is, and it can't do good work if it is being mistreated.

Are you bathing often enough? Getting some form of healthy, non-punishing exercise? Is there some medical issue you have been ignoring? Physical discomfort and neglect will not help you to write again.

Maybe you are too busy to do these things. If you are too busy to do them, you are too busy to write. If you are too busy to rest your sprained ankle, you are too busy to go for runs, and if you are too busy to rest your burnt-out brain, you are too busy to be forcing said brain to produce words.

Step 3: Consume.

Read books, watch movies, play video games. Maybe read something you haven't tried before: manga, webcomics, fanfiction, plays, classic literature, poetry, myths from a culture with which you are not familiar. Try a movie or a television series in a foreign language, or that was made decades before you were born, or that is far out of your usual genres; you can always come back to what you love if you don't care for it. Binge something, and remember how great it feels to get lost in a story. Forget about analysing themes or tracking character arcs: turn your writer-brain off for a while and and just absorb stories, the way you did before you began writing them yourself.

Your creativity tank is empty and your soul is exhausted. Let them rest and refuel.

Step 4: Do something else.

Are you yearning to do something creative but the words just won't come? Create something else: knit, cook, sculpt, paint, plant. Dabble in a new hobby or revisit an old one, or focus on one that you already do that isn't writing. Paint can be a great way of producing something quickly, with immediate visual results. Needle-felting is a nice way of handling soothing materials (wool) while making cathartic stabbing motions (but at some point you will stab yourself, so be prepared for a little bit of pain). Lots of fibre crafts involve soothing, repetitive movements.

Spray-paint something you already own. Shift some furniture around. Pick a home improvement project and work on it until it is complete. Experiment with all the settings on your camera. Try making those recipes you bookmarked ages ago. Fill the biggest piece of paper you have with doodles of dragons or dogs or daisies. Do anything that is not writing.

You can even pair this with some self care as mentioned in Step 2: go for some long walks or hikes, get a really nice haircut, dye your hair, try a different style, get a massage or manicure, go to a sauna or a meditation retreat or take yoga or boxing classes for a month. Experiment with fashion or makeup.

Two things:

1. Make sure your project is something you can complete, or that doesn't need to be completed. This is not about making more work for yourself or adding frustration to the pile of frustrations you already feel.

2. I strongly recommend that whatever you choose be something that gets you out of your head and has nothing to do with words.

Step 5: Ease yourself back into writing, very slowly.

After doing all of the above, or at any time during the process, you may be champing at the bit to write, but when you try the words still will not come. That's extremely frustrating, but normal. Let yourself feel frustrated, but do not dwell in the feeling: the more you dwell on it, the more your brain will associate writing with frustration, and you may end up setting up a feedback loop wherein your brain focuses more on the frustration of not writing than it does on actually writing.

So, one day, when you are feeling less burned out and more alive, take a peek at a manuscript you are writing. If you feel a wave of frustration, reluctance, grief, nausea, or any other unpleasant feeling, close the manuscript immediately and do something else. This is to prevent your brain from associating writing with unpleasant emotions.

A few days or weeks later, whenever you feel ready, take another peek at the manuscript. If nothing comes to mind within five minutes, close it and do something else. Don't force it: if your brain isn't ready to write, it will not write. Revisit the previous steps.

Eventually, you may find yourself scrawling a few words. What a thrill! Your Winter is over!

No, it's not. This is the equivalent of being able to take a few steps, unassisted, on your healing ankle: you are not ready to go for a run, nor even a little stroll down the road; in fact, you probably shouldn't go further than the other end of your house. Did you produce one little sentence? Excellent! That's enough for today. Don't let yourself sit there and cudgel your poor tired brain in the hopes of wringing more out of it. All that will do is make you hate yourself and your brain and your writing.

At this point, you are not "trying to write": you are offering your brain the opportunity to give you some words if it feels that it would like to do so, in a no-pressure environment. Do not order your brain to write: invite it, casually, to jot down a few words if it feels so inclined.

Remember, you have been suffering from burnout. Your brain has been scared and sad and exhausted and frustrated. Do not make demands of it: talk to it kindly.

In summary: do not try to push through the block. This is like trying to sprint on a sprained ankle. If you could write, you would be writing. You can't. Your brain is tired. It needs to rest. This happens to all of us. Admit that you are not superhuman, accept that you are burnt out and tired and sad, make your peace with it, and take a nap.

These two articles contain more advice, and some suggestions for easing yourself back into writing; however, I cannot emphasise enough that you must rest and refuel first.

Why It’s Okay Not To Write (& Simple Steps To Start Writing Again)

Writing Decongestant: 10 Ways To Unblock Your Writer's Block (Contains coarse language.)

You may also like to look at my 'writer's block' tag on Tumblr. In particular, this post (warning for coarse language) by user elidyce discusses four different types of writer's block and the solution to each. You will note that this blog post refers to the fourth type: The Blocked Writer.

If you are experiencing a Winter, be encouraged: you are not the only one to have felt what you are feeling, and it will not last forever. You will write again. And you can hasten that day by not writing now.