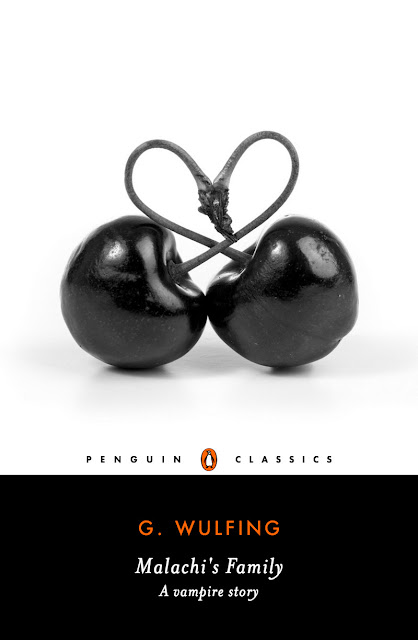

This is a fake book cover (made with the Penguin Classics Cover Generator) for my short story ‘Malachi’s Family’. The Penguin Classics Cover Generator is fun, and very easy to use.

You have reached the blog of G. Wulfing, author of kidult fantasy and other bits of magic. Visit my Smashwords page (linked below) to view my e-books, help yourself to the free ones, and subscribe to this blog or follow me on Tumblr for announcements of new ones.

Wednesday, 30 November 2022

Fake book cover for 'Malachi's Family'

Short story: Malachi's Family

Malachi's Family

G. Wulfing.

January, 2016.

————

Content warnings: attempted kidnapping, blood, violence, death.

————

On a warm, early Summer afternoon, four dirty, scruffy but well-equipped men trudged along a path through farmland, not far from a village. Their skins were deeply tanned under the dirt, and they wore daggers and curved, short swords. Jewellery glinted on their work-hardened bodies and in their hair, inexpert tattoos stained their skins in multiple places, and their hair was either braided, dreadlocked, or shaven completely.

One of them noticed a few children playing in a long-grassed field, on the other side of a bank that ran alongside the path. After a moment, he quietly pointed them out to the others, and the four men became stealthy as they approached the field, using the bank as cover.

There were three children, all blonde, and none looked over seven years old, dressed in simple tunics and trousers. There was a grove in the field, a short distance from the bank, and in the shade of the trees a man lay half-curled on his side, partially obscured by the stalky grass, apparently dozing or asleep; perhaps thirty or forty years old, tall and lean, with black hair and pale skin. He appeared unarmed, wearing trousers and a tunic in washed-out dark blue linen, with a black sash.

The four dirty men looked at each other, and with a few whispered words and some gestures, made their plan.

The children looked up as the men appeared swiftly at the top of the bank. They would have gazed in curiosity, but the men were already swooping upon them, booted feet crushing the long, half-dry grass, seizing the children around their waists, while a shaven-headed man, his curved sword drawn, ran straight for the dark-haired adult lying under the trees.

Terrified and bewildered, the children screamed. One of them shrieked, “Malachiii!”

The shaven-headed man was upon the dark-haired one in only a handful of strides, but suddenly his quarry had leapt to its feet and was standing upright, facing him, half a head taller than he, snarling and glowering straight into his eyes. A low, loud rumble or growl seemed to reverberate in the air: less a sound and more a vibration: an inhuman noise.

The dark-haired man’s clear grey eyes suddenly glowed red, and slim but very pointed fangs had appeared behind his bared upper lateral incisors.

No — not human at all. It was a vampire.

One of them noticed a few children playing in a long-grassed field, on the other side of a bank that ran alongside the path. After a moment, he quietly pointed them out to the others, and the four men became stealthy as they approached the field, using the bank as cover.

There were three children, all blonde, and none looked over seven years old, dressed in simple tunics and trousers. There was a grove in the field, a short distance from the bank, and in the shade of the trees a man lay half-curled on his side, partially obscured by the stalky grass, apparently dozing or asleep; perhaps thirty or forty years old, tall and lean, with black hair and pale skin. He appeared unarmed, wearing trousers and a tunic in washed-out dark blue linen, with a black sash.

The four dirty men looked at each other, and with a few whispered words and some gestures, made their plan.

The children looked up as the men appeared swiftly at the top of the bank. They would have gazed in curiosity, but the men were already swooping upon them, booted feet crushing the long, half-dry grass, seizing the children around their waists, while a shaven-headed man, his curved sword drawn, ran straight for the dark-haired adult lying under the trees.

Terrified and bewildered, the children screamed. One of them shrieked, “Malachiii!”

The shaven-headed man was upon the dark-haired one in only a handful of strides, but suddenly his quarry had leapt to its feet and was standing upright, facing him, half a head taller than he, snarling and glowering straight into his eyes. A low, loud rumble or growl seemed to reverberate in the air: less a sound and more a vibration: an inhuman noise.

The dark-haired man’s clear grey eyes suddenly glowed red, and slim but very pointed fangs had appeared behind his bared upper lateral incisors.

No — not human at all. It was a vampire.

————

A moment later, the last corpse fell from the hands of the vampire, its neck having been emphatically broken. The vampire cast a look around himself, to ensure that all four of the twitching corpses around him were indeed corpses, their heartbeats gone. He rearranged his tongue in his mouth, feeling his fangs withdraw, tasting the slavers’ blood on his teeth. Then he looked for the children.

They were cowering among the trees. He could see their clothing protruding, and hear their frightened breathing. It seemed as though they hadn’t watched the end of the violence, which was good.

The vampire took a few steps toward them, sandals rustling the stalky grass.

“It’s over,” the vampire called calmly. “You’re safe now. They’re all gone.”

‘Gone’ was perhaps a euphemism — the broken, bloody bodies were certainly not gone — but the children would know what he meant. The slavers themselves, with their evil intent and greedy hearts, were gone.

The children hesitated. One of them peeked fearfully around the trunk of a tree. The vampire held out his hand.

Brown eyes wide and tearful, the child stared at him. “It’s fine,” the vampire said reassuringly, hand still extended. His voice was deep and modulated.

The child did not look reassured, edging back behind the trunk, her gaze flicking briefly down to the vampire’s chest. The vampire glanced down at himself and realised that he had blood spatters on his linen tunic, smears of blood on his hands, and probably more spatters on his face. This would not be helping to alleviate the children’s fear.

The vampire strode back to the bodies and picked up the nearest reasonably clean-looking garment: a red cloth cap. He wiped his mouth and lower face on it unsatisfactorily before dropping it. Realising that he would still have blood on his teeth, he snatched up a canteen from the belt of one of the dead slavers, unstoppered it and took a large mouthful, not caring what the fluid was. He swished the tepid water around his teeth and tongue, washing out his mouth, before spitting it out onto whatever grass or human body lay beneath him. He used more water to wash his face and hands. Then he stoppered the canteen, more to be tidy than for any other reason, and dropped it back beside its erstwhile owner’s body. He wiped water off his face with his hands, rather than using his blood-spattered sleeves. Then he approached the grove again.

“Children. You’re safe. It’s all over.”

He knelt in the grass, several paces from the trees, and waited.

“Malachi?” a small voice wavered timorously, after a moment.

“Yes?” the vampire responded calmly.

A different pair of brown eyes peeped at him.

Still Malachi waited. The sun and breeze began to dry the remaining moisture from his hands and face.

At last, the youngest of the children sprinted toward him, and even as Malachi opened his mouth to warn her that she might get blood on her if she touched him, her arms were wrapped tightly around his neck and she was half-sitting in his lap, snivelling her confusion and fright. The other two children followed immediately, clustering around him like chicks around their mother hen.

“M-M-Malachiii!”

“W-Why did they try to grab us?!”

“M-Malachi, I’m scared!”

He hushed them, soothed them, hugged and reassured. The older two glanced toward the bodies, found that their horror overcame their curiosity, and buried their faces in Malachi’s shoulders, blood spattered tunic forgotten or ignored.

The vampire would have let them inspect the bodies if they had so desired — he would have told them that this was what happened to bad people who tried to hurt the friends of vampires — but they clearly did not want to, and that simplified things.

“Shall we go home?” he asked, when the majority of the tears and panic seemed to be over.

The children nodded fervently, and Malachi shepherded them home. He would have walked in the rear as usual while the children skipped and scampered ahead or wandered alongside his long legs; except that this time they clung to him, gripping his fingers uncomfortably tight, casting nervous glances in all directions across the countryside. They no longer felt safe here, Malachi realised. Their wide playground of fields and hedges, in which the most dangerous thing that lurked was a poisonous toadstool or a stinging insect, was now a theatre of threat. The slavers had barely touched the children’s bodies, but they had done permanent harm to their minds.

Malachi wished he could have killed the slavers before they had ever set eyes on the children.

And while the children clung to Malachi as their ‘safe place’, even he was not truly safe to them now. He had killed in front of their eyes. The blood of humans was on his clothes. Their guardian was a killer, and though they held his hands, Malachi could see in the eyes of the older two children that they now feared him a little, too.

They would never be able to trust him quite the way they had before.

He hoped that the slavers would know no peace in the afterlife. People who robbed children of their peace of mind deserved to never feel peace again.

When the children’s home on the outskirts of the village came into view, the children let go of Malachi’s hands and sprinted for it as though they were being chased.

————

“Slavers?! Here?!”

The parents’ eyes were wide and their faces pale. They stood in the kitchen, the two older children clinging to their mother, while their father held and hugged the youngest, who was whimpering on his shoulder. Sawdust and wood-shavings dusted the man’s clothing: he had come straight from his workshop at the side of the house upon hearing his wife’s troubled summons.

“There were only four of them. Merely a roving band of villains. Opportunists. Not organised.”

“Did you — did you kill all of them?” the father asked.

The vampire frowned slightly and lifted his nose a little, his pride offended. “Of course. I said there were four of them, didn’t I? If there had been more, I would have killed more. There were four slavers, and now there are four corpses.”

“Thank you,” the mother said fervidly. “Thank you. Oh, Malachi … I can’t … oh, Malachi …” Her voice became choked, and she knelt and hugged the two elder children close.

The father’s eyes had filled with tears, and he clutched his youngest child tightly. He nodded his agreement with his wife. “Thank you,” he whispered, clearly unable to say more.

Malachi inclined his head in acceptance. He was glad of what he had done, and it had not been difficult; but he would always regret that it had been required.

He glanced again at the children, and again he execrated the slavers in his mind.

Then he turned to leave the family to their emotions for a while.

————

An hour later, the children’s father found Malachi in the small orchard at the back of the house, picking cherries and placing them into a basket on his arm. Malachi, now wearing a clean outfit, acknowledged him with a look, and the human man cleared his throat and spoke, a little huskily.

“We can’t thank you enough for saving our children, Malachi. We can never repay you for that.”

“You don’t have to. We have a pact, do we not?”

The father nodded.

“… We didn’t expect … I suppose we didn’t expect that you would have to kill to maintain it,” he said, after a brief pause.

“My part of the bargain is to protect your family, and that is what I did,” Malachi reasoned simply.

He added, “If I could have killed the slavers before they even touched the children, I would have done so.”

The carpenter nodded. There was a pause.

The vampire continued to select and pluck cherries.

The father was massaging the inside of his left elbow slightly. He took a deep breath and lifted his gaze to Malachi’s face. “This was a good bargain.

“I know there are some who think it strange that we associate with you, but if all it takes to keep my family safe is a few mouthfuls of blood, I would give it a hundred times over. I would give all of it to secure for them a guardian like you.” He held the vampire’s gaze. “They may have nightmares for weeks; they may never feel completely safe ever again; but because of you, my wife and I will be there to comfort them. If it weren’t for you, Malachi — If it weren’t for you —” the man’s voice cracked — “we wouldn’t have them at all. And I would never sleep again.”

The vampire gave a slow, gracious nod of acknowledgement.

There was another, longer, pause, during which Malachi resumed his picking.

Then the human man fidgeted slightly. “What — What shall we — Do you … Erm, have you any need for the bodies?”

The vampire looked at the carpenter, a little superciliously. “Do I want their blood, do you mean?” The human nodded, and the vampire made a noise of scorn. “Tchah. As if I would drink from scum like that.

“Besides, I already have everything I need.”

As he reached upwards for the next cluster of cherries, he looked over his shoulder at the human man, and though his lips were not exactly smiling, his clear grey eyes were shining.

————

End.

End.

————

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)